After a state Supreme Court ruling, Monroe prisoner Arthur Longworth had his sentence reduced for the killing of Cynthia Nelson, 25.

EVERETT — After over three decades behind bars, Arthur Longworth wrote he had “mass incarceration sewn into my flesh and bones.”

“I can’t turn away from it or choose not to know it, and it leaves me with little or no capacity for hope,” he wrote in 2015. “It buries me. It keeps me from breathing.”

Longworth was originally sentenced to life without the possibility of parole in 1986, for killing Cynthia Nelson in an ill-conceived Seattle robbery plot and dumping her body in Snohomish County. She was 25.

Longworth was 20.

But as he sat in court Tuesday, the defendant, now an award-winning writer, had reason to hope.

And since he has already served years more than that, he’ll soon be out of prison.

He’s now 57.

A state Supreme Court ruling last year opened the door for Longworth’s upcoming release. In the decision known as Monschke, the court ruled judges must consider the age of defendants in sentencing.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that “children are constitutionally different from adults for purposes of sentencing.” In Washington, the Monschke decision extends that thinking to 18-, 19- and 20-year-old defendants. It is part of a broader reform movement to give more leniency in sentencing for younger people, whose brains are still developing.

In Longworth’s case, his maturation was further stunted by repeated abuse as a child at the hands of both his parents and foster care providers. While in prison, he has become an advocate trying to stem the pipeline from foster care to incarceration.

Longworth isn’t the first Snohomish County defendant to get another chance under Monschke.

Last month, Aaron Howerton had his life sentence reduced to 27 years in the killing of Wilder Eby, of Mount Vernon. The Monroe man was 18 when he murdered Eby in 1994. Like Longworth, Howerton also suffered abuse as a child.

And Eric Krueger has resentencing scheduled for next month in the killing of two Marysville men in 1997. He was an accomplice in the aggravated murder. He was 20 at the time.

On Tuesday in Snohomish County Superior Court, Nelson’s niece said she feared the Monschke decision “will be opening the wounds for so many families who have already suffered greatly from those who’ve committed violent acts against them.”

As she spoke, Longworth rubbed his eyes with a tissue.

‘Four o’clock, Art Langworth’

Cynthia Nelson worked a side job in sales at Amway.

On Feb. 15, 1985, she planned to meet a former coworker from an accounting firm, according to court records. She was going to talk with him and his sister about a job at Amway. He went by Art.

Around 3:30 p.m. that day, Nelson called her aunt’s house and asked if she could have her calls forwarded there for the next few hours.

About four hours later, an employee at a waterbed store in Seattle threw some broken toys in a parking lot dumpster. The next morning, he tried to retrieve them from the trash for an art project. He found a purse hidden in a cardboard box.

Inside he discovered a checkbook, wallet, driver’s license, glove and a few other items. Nelson’s name was on the ID. The waterbed store manager dialed the number on the ID. The manager talked to Nelson’s aunt and decided the employee should call 911.

One of the Seattle police officers who responded to the call found a datebook in the purse. One entry stuck out.

“Four o’clock, Art Langworth, Pancake House, Desry,” it read, according to court documents.

“Desry” referred to Longworth’s sister.

One day after she was last heard from, a jogger found Nelson’s body floating in the Little Pilchuck Creek near Lake Stevens. An autopsy revealed an 8-inch long stab wound in her abdomen. There was no evidence of sexual contact.

At that spot the night before, a mother and daughter had seen a blue car parked off the side of the road, near the creek. With the help of headlights, the mother witnessed a man walk toward the back of the parked car. She described him to investigators as tall and thin with light hair.

A few days later, police found the victim’s blue Datsun in Seattle’s University District, with the keys in the ignition.

The witness later identified Longworth as looking like the man by the creek Feb. 15, 1985.

Detectives arrested him. He was charged in March 1985.

In a psychological evaluation a month later, Longworth was described as a “five year old dressed up in his father’s suit, who dreams he is a grown man, but inside himself feels frightened, helpless, weak and very small.”

In a trial the next year, he denied killing Nelson, a move he made at the urging of his public defender at the time, Longworth said Monday. A jury convicted him of aggravated first-degree murder. He was sentenced to life in prison — a term Nelson’s family still supports.

“She did not have an opportunity to marry, create a family of her own or continue to take part in the lives of the rest of her family,” Nelson’s sister, Sandra Rodgers, said in court Tuesday. “No part of what happened to her was her choice. Longworth, on the other hand, has had the opportunity to get a college education, marry, have a family, become a property owner, connect with his family members and every bit of what happened was due to his choices, decisions and actions.”

Longworth has since admitted to the killing.

“I’ve always really been just genuinely horrified by the crime that I committed,” he said Tuesday.

He explained what happened in an interview with a psychologist last year. Around age 11, he began engaging in petty crime to feed himself, according to court papers. So he contacted Nelson about the job as a ruse to rob her, he said. In the interview, he later recognized the plan was “bone-headed” because Nelson could identify him. Longworth was desperate.

At first, he left her body there. But after a few hours, he came back to cover up the crime. Longworth said he pushed Nelson into the passenger seat and started driving. He eventually made it to the Little Pilchuck, where he disposed of the body.

Then Longworth wiped down the vehicle, parked it near where he lived in Seattle and left the keys in the ignition. He wanted it to be stolen.

Before the murder, Longworth had prior charges for robbery and burglary.

“I don’t know why he was even out of prison,” Snohomish County sheriff’s detective Jim Scharf said in an interview this week.

Nelson’s sister wondered the same.

Longworth agreed.

“I should’ve been locked up at 18,” he said. “I needed help. I was raised to be an animal and that’s what happened.”

‘No matter what happens’

In his first decade or so in prison, Longworth incurred almost 100 infractions.

In the psychological interview, Longworth explained he felt he needed to be “crazy and unpredictable” to protect himself, according to court documents. He also said he had no hope and little chance of getting an education behind bars.

Violations ranged from threats to theft to assault to possessing a weapon. Often his punishment was solitary confinement.

Longworth got married in 1994. His conduct improved. Moves to several prisons across Washington before landing at Monroe strained his marriage. He divorced in 2015.

Over the past 20 years, Longworth has gotten about a dozen infractions for lying to corrections staff, fighting and not following rules, according to court records.

Longworth only made it to seventh grade as a child. In prison, he studied Spanish and Mandarin, and he has become a Spanish interpreter for the Department of Corrections.

Longworth earned his GED and associate’s degree. He later became an acclaimed writer, with work published in national outlets: the Marshall Project, Vice and BuzzFeed. He writes about prison life and tries to highlight what can often be secretive institutions. He has won several national PEN writing awards. And his work has been read onstage by novelist Francine Prose and rapper Talib Kweli, among other literary figures.

In 2012, Longworth petitioned for clemency, one of his first glimmers of hope, he testified Monday. Until then, he’d resigned himself to life in prison.

“You don’t think I’m tough enough to sit this out until I die?” he said. “I’ve had to accept that since I was young. So I’m fine. I’ve got this, no matter what happens.”

Snohomish County’s prosecutor at the time, Mark Roe, opposed the petition, arguing Longworth still wasn’t completely honest about the killing in an interview with the detective, Scharf, just ahead of the hearing in 2012.

The clemency board denied Longworth’s petition. He was “pretty devastated,” he said this week.

On Monday, a former prisoner, Herbert Blumer, alleged under oath that Longworth asked him on multiple occasions behind bars if he knew anyone who could kill Roe.

Also under oath this week, Longworth denied any murder-for-hire plot, saying Blumer was known as the “prison informant.” Superior Court Judge Anna Alexander ruled she wouldn’t use this allegation in her resentencing decision. She said she didn’t find Blumer credible.

The psychologist who interviewed Longworth last year, Dr. Brian Judd, wrote in his report that the defendant is a “high risk for future violence.” Over three-quarters of those who scored similarly to Longworth in an assessment were charged with a violent offense within five years of release, Judd wrote. At 12 years, that number had risen slightly to 87%.

“If he gets out, I’m concerned he’s going to continue his criminal activity,” Scharf said.

However, with each passing year without reoffending, the chances of Longworth committing a violent crime decrease by about 10%, Judd noted. If paroled, the psychologist argued, the defendant “would warrant a higher allocation of supervisory resources than a typical offender.”

Other men who served time with Longworth told the judge he was a helpful and selfless leader who made them better people.

“We have all watched him consistently carry himself with a positive attitude, determination to assist in changing people’s lives and a dogged focus on continual self-improvement,” said Devon Adams, who met Longworth in Monroe in 2009.

‘Free people clothes’

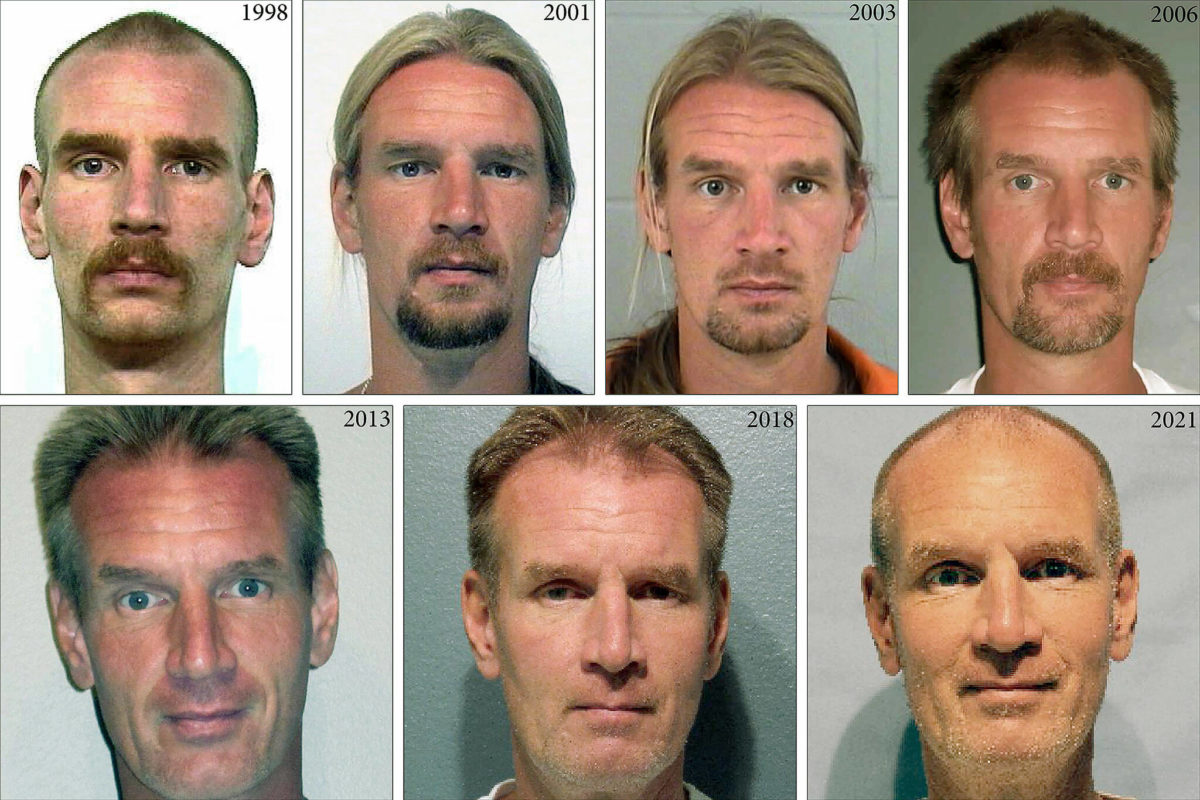

Exactly 37 years after Nelson’s murder, Arthur Sean Longworth sat in court on Tuesday. His hairline has receded and his face appeared somewhat wrinkled. Still tall and thin, he wore a pale button-up shirt and a black tie.

“It feels weird to sit here in free people clothes,” Longworth said in court. “I’m not used to it because I do not know what it’s like to be outside of prison. But I do know that I would be able to do a lot of good outside of prison. More good than I can inside of prison.”

He apologized to Nelson’s family for his “indefensible” actions.

Prosecutors pushed for Longworth to be resentenced to 45 years. Longworth’s public defender, Jennifer Bartlett, argued for 30 years.

Judge Alexander started her remarks Tuesday afternoon by addressing Nelson’s family, saying she heard them.

Cynthia Nelson, the judge said, “did not have a chance in the last 37 years to smile and to inspire others and to develop the emotional intelligence and health and she didn’t have a chance to lead people, and she didn’t have a chance to learn Spanish and Mandarin and she didn’t have a chance to learn to write powerfully and love others and to inspire love from new people.”

The judge continued: “And she didn’t have a chance to, maybe one day, save a life herself because Arthur Longworth took her life, and with it, he took part of your life, too.”

But she sided with the defense in revising Longworth’s sentence to 30 years. She said he came before the court as a “changed man.”

He’ll be on probation for five years.

Court papers say Longworth plans to live on a 40-acre ranch in Pend Oreille County in northeastern Washington. He bought the property with money from a $750,000 legal settlement, in a lawsuit over abuse he suffered at a boys home.

The land has a creek and a beaver pond, his younger sister Regina Godwin said in court Tuesday. Longworth wants to start a nature therapy program there.

“I have lived on the ranch for a couple of years now,” she said. “I hope Art will join us soon.”

Jake Goldstein-Street: 425-339-3439; jake.goldstein-street@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @GoldsteinStreet.