Our survey of all 50 states and the BOP reveals that prisons make it hard for people to qualify as indigent—and even those who do qualify receive limited resources.

Our survey of all 50 states and the BOP reveals that prisons make it hard for people to qualify as indigent—and even those who do qualify receive limited resources.

by Tiana Herring, November 18, 2021

Many people in prison struggle to purchase basic hygiene supplies, stamps, and other necessities of incarcerated life—thanks in part to the low wages they made before entering prison and the mere pennies they earn working behind bars. Most prison systems claim to provide assistance to people who are extremely poor (or, in correctional policy terms, “indigent”). However, our new survey reveals that these “indigence policies” are extremely limited—both in who they help, and the amount of assistance provided.

We found that in almost every state and the federal prison system, incarcerated people must maintain extremely low balances in their “inmate trust funds” before receiving any help with essential items like soap and stamps. And being deemed indigent is only half of the battle, as many states provide very few resources even to those who do qualify. What’s more, in 18 states, the assistance given to indigent people is actually treated as a loan they must repay if their account balance ever goes up, meaning that people are required to go into debt for access to basic necessities.

We gathered information on indigence policies in all 50 states and the federal Bureau of Prisons by looking through state departments of corrections’ websites and contacting public information officers in each system. Here, we offer answers to two questions:

- How is indigence is defined in each state?

- What items or services are supposed to be provided to indigent incarcerated people, according to state policies?

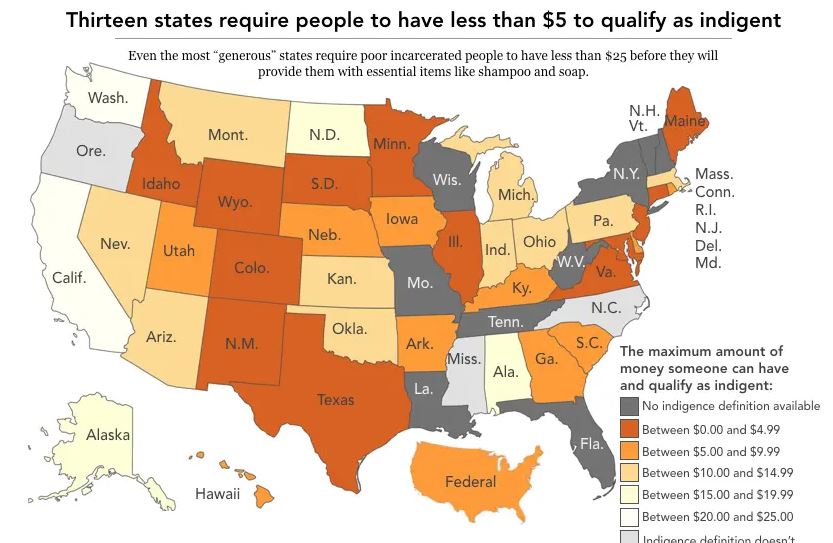

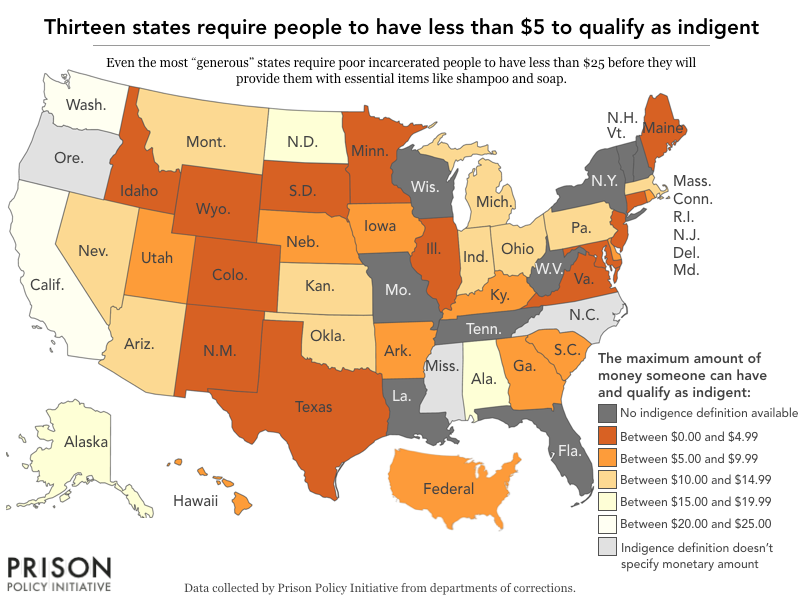

Most states have very narrow definitions of who qualifies as “indigent”

We were able to find a definition for indigence in 41 states and the federal Bureau of Prisons. The remaining nine states did not have easily accessible definitions online, and were not able to provide us with the requested information when asked. The lack of transparency is disappointing, and makes it difficult to hold prisons accountable for doing the bare minimum to support the poorest incarcerated people. Worse, this inability to produce policy information may be an indication that some states do not have indigence policies, meaning extremely poor incarcerated people in these states might not receive any assistance at all.

Every single department of corrections with an indigence policy requires people to have very little money before they can qualify.

Every single department of corrections with an indigence policy requires people to have very little money before they can qualify. The monetary thresholds for indigence status range from a low of $0 (meaning that people with $1 to their name would not be considered indigent) to a maximum of $25. Over half of states have their limits set between $0 and $10. Additionally, most states require that people keep these low balances for at least a month before qualifying. If someone does get money added to their account that exceeds the indigence limit, they lose their indigence status and have to wait before they can be considered indigent again. In New Mexico, for example, an incarcerated person must have $0 in their account for a month before they qualify as indigent. Going so long with such low account balances means that people are surviving on severely limited access to food and basic necessities like toilet paper. While 30 days was the most common wait time – and certainly too long to have to wait for soap and envelopes to write home – Alabama, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Utah all require people to wait even longer, from 45 to 90 days.

These arbitrary limits on the amount of money people can have means that people can lose their “indigence” status—and therefore their access to necessary supplies—just because they received a small deposit from a family member or for working a prison job. Many indigence policies specifically prohibit deposits and income of any amount in their definitions. For example, an incarcerated person in Maryland making 15 cents an hour for their labor can’t qualify for indigence status; while $0.15 an hour will hardly make someone rich, people are not allowed to work and receive free access to indigent supplies. These policies often ignore that many incarcerated people have automatic deductions taken from any money deposited into their accounts, including for fines and fees, involuntary savings funds, or repaying the department of corrections for items they received previously while considered indigent.

We also found that four states put additional work-related requirements on who can qualify for indigence, by limiting the status to those who are incapable of working, are “involuntarily unemployed,” or are actively seeking work.

The fact that free basic supplies are provided only to the poorest people—and not to all incarcerated people for free by default—fits with correctional trends of shifting the costs of incarceration onto incarcerated people and their families, as also evidenced through the rise of paid services like tablets and phone calls.

The services offered to indigent people vary from state to state, but they are always very limited

The most common items provided to indigent incarcerated people are hygiene kits and supplies for sending a limited number of letters to loved ones; the number of free letters allowed range from one per month in Ohio to seven per week in Maryland. Legal mail is also mentioned in many policies, though departments of corrections are more likely to require repayment for these mailings. In some states, people have to choose between using their mail supplies for personal or legal mail, as they aren’t always considered separate services.

Eighteen states require indigent people to pay the department of corrections back for at least some of the services they receive while deemed indigent. In at least seven states, correctional agencies don’t appear to offer any services or supplies for free without the expectation of repayment. The Department of Corrections in Washington State, for example, covers the cost of mailing up to 10 letters per month for indigent incarcerated people. However, if the indigent person ever loses their indigence status, the department will recoup the costs for any letters previously mailed for free by deducting money from their “inmate trust accounts.” In states with repayment policies, the only way for the poorest incarcerated people to stay out of debt is to simply not write letters to their families, despite the fact that communication is crucial for maintaining family ties and increasing the chance of success upon release.

Every prison system can—and should—do more

Every indigence policy we looked at could be improved, but some states have implemented a few decent practices (at no cost to incarcerated people or their families) that others could consider adopting:

- Seven states allow indigent incarcerated people and their families the opportunity—though often very limited—to communicate via phone calls, video calls, email, or texts free of charge.

- Seven states clearly state that feminine hygiene products are provided to those who need them, free of charge.

- Seven states specify that toilet paper is provided to indigent incarcerated people for free.

- New Jersey provides indigent incarcerated people with a $15 monthly allowance for commissary, which is important for access to food and basic necessities.

- California’s code of regulations prohibits charging indigent incarcerated people for mailing services they received while considered indigent (including the cost of materials, copying, and postage) if they lose indigent status.

Stringent indigence policies punish the poorest people in prison by severely limiting the amount of money people can have and still receive free services, dictating how they can spend the little money they do have, and making them wait weeks in extreme poverty before offering help. All incarcerated people deserve, at minimum, access to hygiene items and ways to communicate with loved ones without having to take on even more debt.

Footnotes

- Incarcerated people had a median annual income prior to incarceration that was 41% lower than non-incarcerated people of similar ages. Unfortunately, this national data is not available for individual states. ↩

- All states that have indigency policies require unreasonably low balances, but nine states did not share them with us, and therefore may not provide any support to people unable to purchase necessities. ↩

- The term “inmate trust fund” – also called a “trust account”—is a term of art in the correctional sector, referring to a pooled bank account that holds funds for incarcerated people whose individual balances are sometimes treated as subaccounts. The term “trust” is used because the correctional facility typically holds the account as trustee, for the benefit of the individual beneficiaries (or subaccount holders). ↩

- Prison cafeterias often serve small portions of unappealing, nutrient deficient foods. As a result, most of the money people spend in the commissary goes toward purchasing extra food. Formerly incarcerated people who had little outside financial support report that they experienced constant hunger and a variety of health issues as a result. ↩

- While some departments of corrections may feel wait times are necessary to prevent people from manipulating account balances to receive indigence status, long wait times create unnecessary delays in needed assistance. ↩

- What’s included in hygiene kits varies by state but generally they include soap, shampoo, a toothbrush, toothpaste, and shaving equipment. ↩

- These states include Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, and Wisconsin. ↩

- These states include Maryland, Nebraska, New Jersey, Ohio, Oklahoma, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. ↩

- These states include California, Colorado, Idaho, Nebraska, New Jersey, Oklahoma, and Wyoming. ↩

For the poorest people in prison, it’s a struggle to access even basic necessities to the Prison Policy Blog.