Reducing incarceration is one of the few public policy initiatives where Louisiana’s Republicans and Democrats agree, and have worked in concert for a decade now.

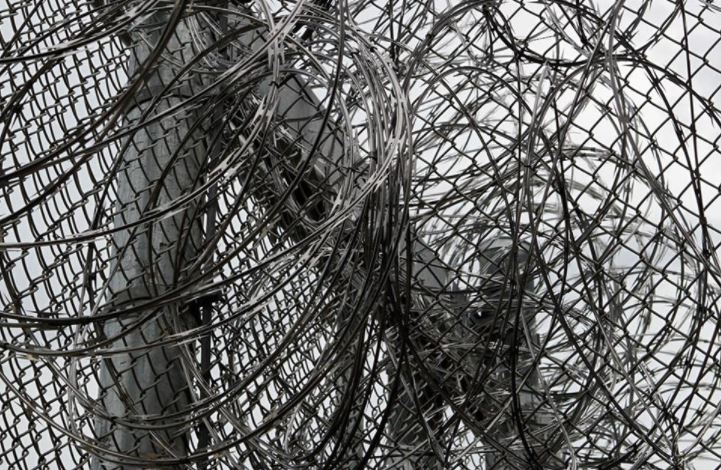

Louisiana often leads the nation in incarceration, slipping occasionally to second place. But we are making progress. The state once imprisoned 40,000 people, but that total has been reduced by about a third, thanks in part to legislation that won support from both parties.

In a state cursed with high poverty and crime, it’s hard to see how we will ever fall below the national average in incarceration. But we don’t have to be No. 1, or even No. 2.

One reason we still rank at the top is the bulging population of lifers in our prisons. Louisiana sentences people to life without parole at one of the highest rates in the nation. There are nearly 4,200 lifers behind barbed wire. Many are there for murder and rape, and Louisiana has the highest homicide rate in the land. But a smaller number are jailed for less severe crimes, like purse snatchings or child neglect.

How we let that happen was the subject of a deeply reported series of articles by The Times-Picayune, The Advocate and The Marshall Project, a nonprofit newsroom focusing on criminal justice issues.

The reporting focused in part on lifers who committed crimes that seem out of proportion to their sentences.

One was 88-year-old Clarence Simmons. A judge in Caddo Parish convicted him in a one-day trial in 1991 for illegal possession of a stolen camera and tripod, then handed him a life sentence as a four-time felony offender. Simmons celebrated his 88th birthday at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola in a skilled nursing unit, where he is confined to a wheelchair.

He would still be there, but the Caddo district attorney, James Stewart, agreed to vacate the habitual life sentence and Simmons was freed this month.

Other local prosecutors are also revisiting habitual offender life sentences, including Orleans’ Jason Williams and, to a lesser extent, St. Tammany’s Warren Montgomery.

The reporting showed the habitual offender law has been invoked unevenly.

Nearly two-thirds of habitual lifers in the state were sentenced in one of four large parishes: Caddo, Orleans, St. Tammany or Jefferson. And prosecutors have mostly aimed the law at Black defendants. Black people make up 31% of Louisiana’s population, but 66% of its state prisoners, 73% of those serving life sentences, and 83% of those serving life as habitual offenders, corrections and census data shows.

Kondkar, who is assisting civil rights prosecutors in Williams’ office, describes the law as ”an awesome power” in a district attorney’s hands.

Excessive life sentences are the next frontier in the bipartisan campaign to reduce incarceration. Voters and victim family members reasonably expect that killers sentenced to life should serve their full sentences, even in cases where aging and health issues mean they are no longer a threat. But habitual offender laws, many enacted in the 20th century amid legitimate concerns about soft sentences for repeat criminals, have sometimes gone too far, especially in limiting discretion for judges.

If judges are too lenient, the solution is to elect better judges, not to lock people up in perpetuity for crimes that draw smaller penalties in other states.