|

Good morning. Should wrongfully convicted people falsely admit guilt to win parole? |

|

A terrible Catch-22 |

| Jeffrey Clark and Garr Keith Hardin were the victims of an unjust murder prosecution near Louisville, Ky., during the mid-1990s. |

| A jailhouse informant made up a story about one of them confessing. The police did not pursue a lead involving an actual confession to the murder. A dishonest detective — Mark Handy, later discovered to have fabricated evidence — testified against Clark and Hardin. And the prosecutor misled the jury about a fingerprint and a hair sample at the crime scene. |

| The jury convicted the two men, then both in their early 20s, and they were sentenced to life in prison. They would spend more than 20 years there before lawyers for the Innocence Project helped win their release, based on DNA evidence and the exposure of the detective’s dishonesty. |

| At that point, you might have expected the criminal justice system to apologize to the two men and leave them alone. Instead, prosecutors announced plans to try them again for the murder — and even added a perjury charge against Clark. Why? Partly because, in an attempt to win parole while in prison, Clark had decided to admit to the murder and express remorse. |

| Parole hearings create a terrible Catch-22 for wrongfully convicted people. If they admit guilt, they can undermine any attempt to overturn their conviction. If they continue to assert their innocence, they can doom their best chance at freedom — parole — because parole applications effectively require statements of remorse. |

America, apart |

| Joseph Gordon, a 78-year-old man in New York State, falls into the second category. He has already served more than his minimum sentence of 25 years for a 1991 murder, and multiple prison officials and guards have supported his parole application. Gordon has “the character and moral compass to return to society as a productive member of his community,” wrote a former superintendent at Fishkill Correctional Facility, where Gordon is incarcerated. |

| But the parole board has refused to release him. The chief reason, according to the board, is Gordon’s continuing insistence of his innocence. |

| You can read Gordon’s full story in this recent Times article by Tom Robbins. The details of the case are messy and tragic. Gordon clearly committed a crime: He covered up the killing of a 38-year-old doctor who may have been having a sexual relationship with Gordon’s 16-year-old son. Gordon says that his son killed the doctor and the cover-up was an attempt to protect his son. |

|

| “I was not going to put my son in prison,” Gordon said. |

| After reading about the case, I don’t feel confident about what happened. But there are good reasons to doubt that Gordon committed the murder, and his lawyers argue that guilt is no longer the central question anyway. They told me that they are confident he would have been released by now if he had simply abandoned his innocence claim, based on his age, his prison record and the pattern of other parole decisions. |

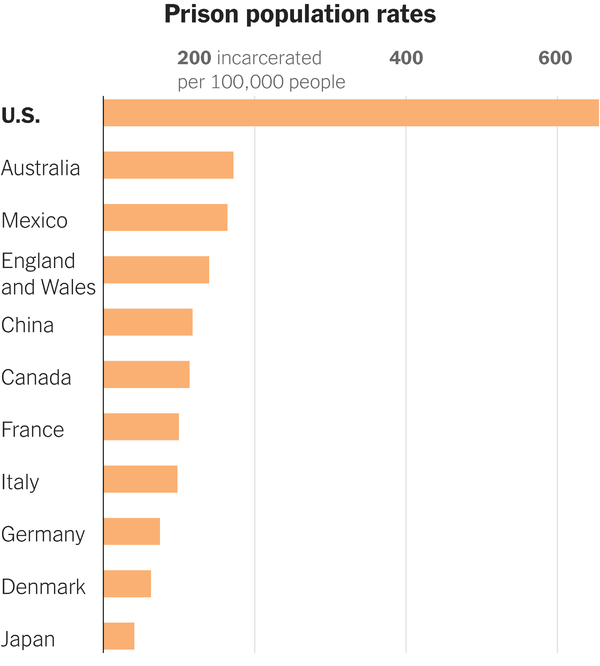

| I want to tell you about Gordon’s case this morning because of the broader problems that it highlights. The U.S. has the world’s largest incarcerated population, with more than two million people in prison or jail. Most other countries take a radically different approach to criminal justice: |

|

Convictions over justice |

| The starkest injustice is the large number of people imprisoned for crimes they did not commit. This morning, tens of thousands of Americans woke up behind bars because of wrongful convictions. |

| Consider that one academic analysis of death row inmates found 4.1 percent of them deserved to be exonerated — an estimate it called “conservative.” Another study, focusing on sexual assault cases, estimated a wrongful conviction rate of 11.6 percent. |

| Whatever the true number, it’s large enough for alarm. Our criminal justice system regularly puts a higher priority on winning a conviction than on achieving justice. And Black and Latino Americans are disproportionately imprisoned as a result, studies show. |

| The biggest policy question is how to minimize wrongful convictions. In recent years, a reform movement — including political conservatives, moderates and progressives — has been trying to do so. Among their ideas: ban testimony from jailhouse informants; require the recording of interrogations; expand post-conviction DNA testing; and increase penalties for prosecutors and police who lie or manipulate evidence. |

| Yet changing the rules around parole can also make a difference, especially given how many unjustly incarcerated people will not be helped by changes that apply to future cases. “People who maintain their innocence remain in an impossible situation,” said Michelle Lewin, executive director of the Parole Preparation Project. |

| Currently, some prisoners decide that their best option is to admit guilt falsely. Huwe Burton offers an excruciating example: At a parole hearing, he dropped his claims of innocence and admitted to stabbing his mother, Keziah, to death in their Bronx apartment in 1989, when he was 16 years old. |

| He had been convicted after police officers coerced a confession from him. They decided to focus on him instead of an obvious suspect — a neighbor who had a violent criminal record and who was discovered driving Keziah’s car six days after the killing. In 2019, a Bronx judge vacated Burton’s conviction. |

| One way to prevent parole dilemmas like Burton’s is for parole boards to make decisions based more on a person’s rehabilitation and risk to the community and less on their stated guilt or innocence. Julia Salazar, a Democrat from Brooklyn in the New York State Senate, has proposed a bill that would do so. |

| The bill has significant support in the legislature, but it remains unclear whether it will become law. Gov. Kathy Hochul has not announced her position on it. |